a piece to return to again and again… haunting and lulling…

(The Wire, UK)

Schaefer has created a consistently engaging body of work that, more often than not, focuses on the relationship between sound and the spaces it both inhabits and creates. For Extended Play, Schaefer created an installation that focused on a score for piano, violin, and cello, with each part recorded separately and pressed onto to vinyl to be played at varying speeds throughout a gallery on record players that would stop in accordance with foot traffic throughout the space.

The first three tracks here wind through the individual instrumental passages themselves, allowing plenty of open space and warm vinyl crackle in between each sparsely placed note and chord. It’s beautiful, haunting stuff, but the real keeper here is “Extended Play — Acoustic Ensemble,” a stunning reworking of the original gallery installation that presents the three instrumental components in context, with each melodic phrase doubling back on itself while dropping in and out of the mix. More than one of Schaefer’s best works, Extended Play is easily one of 2008’s best releases to explore the intersections of experimental electronics and modern composition. Highly recommended.

(othermusic.com)

Janek Schaefer’s work has got better and better over the years in my humble opinion. Following on from last year’s release with Stephan Mathieu he’s produced an album of some substance for Deupree and Chartier’s Line imprint. Using his trademark turntables to create a seris of compositions that are nothing short of beautiful. Layering piano, cello and violin recordings together at various speeds he’s summoned up a sound that’s haunting and incredibly atmospheric. Starting with cello on track 1 through to violin on track 3 and then into a simply gorgeous ensemble using all 3 on track 4. There’s a naturally classical style that comes through, but it’s much, much more than that. The final track, clocking in at 24 minutes, is a wonderful collage which also adds in a recording of ‘Tango Zyczakowskie’ recorded uing a 1940s radio. A timeless and lovingly crafted album that gets a big thumbs up from me.

(Smallfish, UK)

Janek Schaefer’s illustrious career as a sound artist, turntablist and composer has seen various standout moments over the years, from his postal travelogue 7″, Recorded Delivery, on the Hot Air imprint to his collaboration with Stephan Mathieu, Hidden Name. Extended Play ranks alongside Schaefer’s very finest works, and one of his most overtly musical, in the traditional sense. Originally conceived as an installation, Extended Play consists of piano, violin and cello each playing a predetermined score, recorded separately, edited and then cut onto vinyl. The three instruments each had three vinyl EPs cut which were then played back at 33rpm, 45rpm and 78rpm, continuously repeating and pausing briefly according to the traffic of gallery visitors. It all sounds a bit convoluted, but this album makes sense of it all, dividing the work into three individual instrumental studies, plus one ‘ensemble’ recording of the finished installation, which is breathtakingly beautiful, and remarkably composed sounding given the slightly aleatory aspect of all its variables coming together over its twenty-four minute duration. The final piece on the album makes the most explicit reference to the concept that drives Extended Play, tapping into wartime musical codes: the appearance of a scratchy old Polish song during the closing track serves as an example of how the English secret services would furtively communicate messages with the occupied Poles, via song lyrics. Schaefer completes the image with a double exposure of sorts, playing BBC broadcasts over the top of the song, bringing a truly memorable album to a close. Seldom has sound art sounded as enjoyable as this.

(boomkat.com)

On 12K’s sub division Line, a new CD by Janek Schaefer, based on his sound installation ‘Extended Play’. Like with many other things by Schaefer there are many ends to this: his mum’s Polish background, the secret musical messages of the BBC in World War II (the ‘Jodoform’), Polish music, old vinyl and old turntables playing records, nine in total. They play three cello ep’s, three piano ep’s and and three violin ep’s, in varying speeds. The music was taken out of a 1918 song and re-arranged and recorded on the vinyl, so it’s new vinyl with old music. The CD is what it sounded like. The first three pieces are a cello duo, a piano trio and a violin duo, whilst the ‘acoustic ensemble’ takes up twenty-four minutes. Since this deals with war, death and also life, it’s all quite solemn, slow music. It has nothing to with electronics, processing or field recordings, but it’s gentle, minimal music. Music however that is not composed but rather played by itself. The stop gap that happens every now and then is part of it, and adds a strange element to it, but one that works well. This music, had Schaefer been born 50 years ago, could have been easily part of Eno’s Obscure Music series and has a similar, great quality to it as say Gavin Bryars ‘Sinking Of The Titanic’. Similar free form modern classical approach, great conceptual edge and great execution. Highlight all around here too.

(Vital Weekly, NL)

LINE have chosen a somewhat challenging path to walk, in that it sets out to audibly document installation work that very often encompasses physical and visceral elements that can only best be appreciated within the environment they were designed for. It’s a little like looking at one quarter of a painting, and trying to discern it’s overall meaning and physical presence. I have taken issue with this with other labels, and in most cases would have preferred to have seen or experienced the thing live, or certainly as a DVD document to accompany the recording.

Having experienced some of Schaefer’s work live, I can testify to his ingenious and often startlingly simple approach, most of his work being based in or around the use or misuse of turntables, and to be around this installation must have been like confronting a Mark Rothko painting for the first time in all its elemental, vital richness.

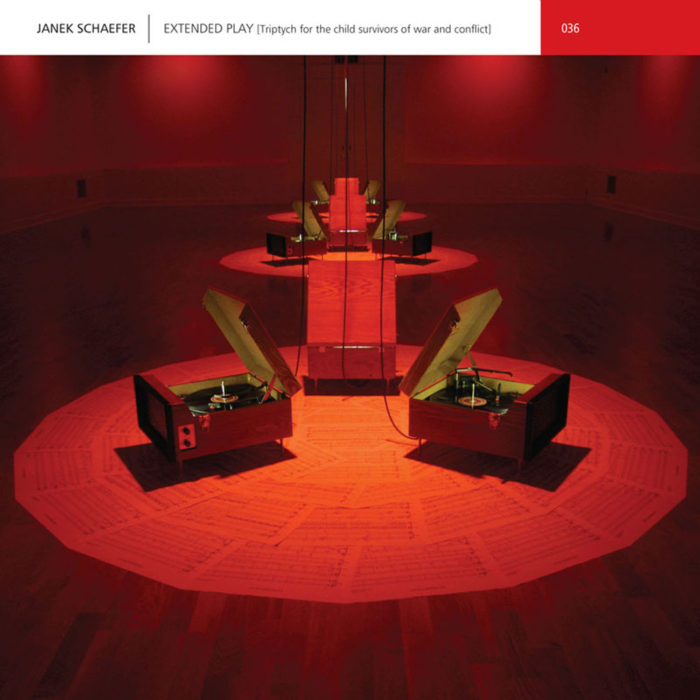

The cover image certainly confirms this, with a set of turntables iconically set up, bathed in red light, a spiritually incandescent glow around them that visually evokes a stark, sombre, yet highly charged atmosphere even before a sound is encountered. Extended Play sets out to celebrate the spirit of hope and renewal taking as its central theme the wartime “Jodoform” cryptic musical language that was broadcast by the BBC world service, and interpreted by the Polish Underground. Schaefer, alongside Michael Jennings, developed a score based on Cello, Violin, Piano, Acoustic Ensemble, and the Jodoform, and cut each segment into vinyl. These recordings were then played at alternating speeds that were triggered to stop playing as the audience moved around them. From this breathtakingly simple premise, emerges a deeply evocative set of atmospherics, charged with melancholy, each piece can be heard “winding down” as the audience move around it, then springing back to life, to restore the continuity of the piece, and rejoin the ensemble. This is an inspiring, and poetic recording that celebrates and commemorates the life and energies of Schaeffer’s newly born daughter, and the birth of his mother, born as she was at a significant point of the conflict in Warsaw..Schaeffer poignantly posits the question, “how opposite can two beginnings be?”

Extended Play is a worthy listen in its entirety, and I was struck with the same sensations that I was when visiting the Anne Frank house in Amsterdam, that within that deep sense of fear, and almost claustrophobic silence, the strength and triumph of the human spirit can only serve to humble and inspire us all, and resonate through time. A fine piece of work for a fine label..essential.

(WhiteLine, UK)

Documenting an installation on disc can’t be easy. A total experience that makes sense within a particular space-in this case, a red-lit room in the Huddersfield Art Gallery-may be diminished by the act of reducing it to mere sound on a CD. And when, as in this case, the piece is interactive, there’s no recreating the audience’s experience of actually participating in making the music. Janek Schaefer’s solution has been to create a special CD version that uses the installation’s sonic elements, but makes several unique and unabashedly constructed pieces out them that downplay the original installation’s chance qualities. It may not be the same as being there, but it has the best possible chance of standing on its own, and in this case the result is a strikingly emotional work.

Extended Play‘s initial inspiration came from a fairly ordinary, yet life-changing moment in Schaefer’s life. When his first child was born in 2005, he got to thinking about the circumstances of his mother’s life at the corresponding age; one infant was born into the weird mixture of safety, comfort, economic insecurity, and random political terror enjoyed by contemporary residents of London, the other into the decidedly harsher and more immediate threats of Warsaw, Poland during WW II. Schaefer’s favorite means of manipulating sounds is the turntable, but he is less performance-oriented than Philip Jeck or your average hip-hop DJ. Rather, he collects sounds, tethers them to ideas, and sees where the two take each other. For the raw material for Extended Play, he lifted some melodies from “Tango Lyczakowskie,” a patriotic Polish folk song that was broadcast by BBC World Se rvice to Polish resistance fighters in order to convey encoded information on the day that his mother was born in 1942. Schaefer and co-composer Michael Jennings fashioned this material into a 10-minute piece of chamber music for violin, cello and piano, then Schaefer pressed each instrument’s part onto a 7″ record.

In the installation version, three record players set to different speeds each play a record of each instrument; motion sensors cut the power to each turntable as a person passes, thereby making each observer a participant in the creation of something they can’t foresee and can’t really control. Of course, such an experience is impossible to create on record, so Schaefer has instead focused on the records themselves. The first three tracks isolate single instruments. Intermittent groove crackle, the occasional thump of a needle picking up and restarting, and the shudder of records stopping when the power’s cut reinforce the inherent melancholy of “Vinyl Cello Duo.” This is minimalism, both in sound and method; not only does Schaefer work with minimal resources (two records), he makes the most out of a few long tones and simple phrases. “Vinyl Piano Duo” is sparser, placing silence on a nearly equal footing with the slightly distorted, gener ously reverb’d piano figures. This could almost be ambient music for a rainy day in a room with a hissy radiator, but the slurs generated by turntable stops and starts disrupt any sustained reverie. The ascending melody reminds me a bit of the licks Robert Wyatt played on Eno’s Music For Airports, but the built-in disruption and heaviness of mood make this the perfect soundtrack for the realities of modern air travel. It’s great, but don’t expect it to come to a terminal near you anytime soon.

“Vinyl Violin Duo” is of a piece with what has come before; the penultimate track, “Acoustic Ensemble,” which was crafted using the original recordings of the instruments played at different speeds. Although it eschews the use of turntables, it might come closest to the installation experience on account of its greater density of event. It’s certainly the most deeply involving and demanding piece of music. 24 minutes long and none too hasty, it requires you sink to into what is essentially a long, oddly cyclic piece of chamber music. The fuller sound and more intricate instrumental interaction also impart a greater emotional complexity. As strings and keys sweep up in pitch, they dispel the duos’ dolor and usher in an aura of hope as well as gravity. The record closes with a collage of the source tune, radio announcements and vintage shortwave noise that gives the whole thing a decided Conet Project vibe.

Schaefer has previously conveyed his anti-war sentiments via song titles, but here it is the music’s evocation of dignity that makes the point. It reminds me of the line in the movie The Lives of Otherswhere a character muses that Karl Marx once said that he couldn’t listen to Beethoven’s “Appassionata” anymore because it made him want to pat people’s heads rather than beat on their skulls. Add this to the music that not only dissents from such methods; it offers visions of gentler way to change hearts.

(dustedmagazine.com)

To the eyes of Janek Schaefer, “Tango tzyszakowskie”, a Polish folk song once enlisted as a pigeon carrying secret messages through the radio-waves for members of the Polish underground during World War II, played no less a magnanimous role in another, admittedly markedly different, event: that of his mothers birth in the year 1942. The circumstances under which his mother was born being as different as they are from those which his own daughter now enjoys brings Schaefer to wonder at this notion of ‘beginning’ and all of its subtleties of gradation.

Schaefer finds in “Tango tzyszakowskie” a short rising musical phrase, and in bringing it to term in numerous ways, enables it to enjoy the possibility of a return. This it did as a part of The Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in 2007. Schaefer’s score was emitted into the room through three retro record players, which were set at 33, 45, or 78rpm, and which would briefly pause in response to audience members as they passed through the exhibition. Apart from achieving a sort of historical significance owing to its origins, with this last point in mind, and the fact that all the while the medium itself can be heard, time passing through the grooves of the record player like rain tracing furrows through the dust, this sound-event also clearly occurs on the surface of the present age.

Both realms are clearly heard, and, in fact, they also interlace to fine effect over the course of the album. The former, that of history and its mournfulness, is heard in the slow, stylized gesture and motion of the instruments, as the nervy edge of the piano furls around the reflectiveness of the strings. But the picture is also a good deal more rich and intuitively complex than such stereotypical roles suggest. The formal poise of each piece contains remarkable fluidity of musical identity, continual transformations of mood and material that defines rather than jeopardizes coherence. The deflections, supple deviations and abrupt interruptions offered up by the device on which the music is played, and through which it is rehabilitated, not only makes this a more eerie, ambiguous experience—the sound so exhibited is now personal and impersonal, fluid and mechanical, disciplined and random—but, at least in part, it brings the music to another plane, a more contemporary one, wherein the medium trumps and ensnares the subject in the empty and functional place which was originally reserved for it.

Indeed, the device levers itself into the unfolding dialogue between piano and strings to such an extent and, similarly, on tracks four and five, the looping and layering of the mix is such that the distinction between triumphant return or arid recurrence is more or less blurred. To be sure, even divorced from it context, the album is quite simply beautiful, but just as for the Polish Underground “Tango tzyszakowskie” harbored a welter of encrypted messages beneath its refreshing refrain, so to does Schaefer’s rendition for us today.

(squidsear.com)

Most people will think of Janek Schaefer as the “guy with the gramophones.” Even Wikipedia open their article on him with the assessment that he is “known for his innovative turntablism” and hardly an interview goes by without somebody mentioning Schaefer’s three-armed record player, which allows him to simultaneously draw different sounds from a single disc. Annecdotes of Vinyl saving his concerts when his laptop break down add to this popular medial image.

On the other hand, aesthetics are less an issue for Schaefer. Rather, he is interested in the immediacy and tactile qualities of the format, allowing for direct manipulations. His background in architecture plays an even more important role. Space is sound to him and after finishing his studies he subsequently went on to research this relationship in various projects, always holding on to his personal creed that “we experience space through our ears.” His music, meanwhile, is an attempt at proving that the reverse is also true… Extended Play, meanwhile, is the audio document of an installation premiered at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival last year. Drenched in intensely enigmatic, darkly-orange light and residing on three islands of sheet paper, nine retro turntables play vinyl records containing solo parts for Cello, Violin and Piano as well as a segment for “Acoustic Ensemble,” where the individual voices merge into a long, floating piece of airy atmospherics. At times, the gramophones briefly pause to allow for the audience to move from one island to the next, changing the parameters of the composition and adding an organically oneiric feeling to the music… It is a feeling mirrored by Extended Play, even though the music could hardly be more different. Transformation is essential to a piece reflecting on the relative happiness of the children growing up in 21st century Europe compared to those born in times of war and conflict. In the beginning, the timbres of the instruments are essential to the music, with especially the “Vinyl Cello” and “Vinyl Violin” duos mainly highlighting single, stretched-out tones with a palpable degree of inner tension.

In the “Acoustic Ensemble” segment, however, the three voices come together in a piece of epic proportions and sonic majesty. Working with deep layers of Piano-reverb, droning Cello-palpatations and bittersweet Violin brushes, this is a 24-minute long, slowed down dream of meditative exhaling. Melodies never come full circle, but their sense of yearning and incompletion is not a dark one, but rather a moment of complete detachment from all worldy demands. If hope could become music, this is what it would sound like.

In which way is the idea that sound can be space important to these two albums? In the case of Extended Play, the notion is certainly more obvious: Three small-scale recordings combine into a work of borderless outlines by subtle use of reverb, a nonlinear choreography of musical events and slow, almost casual gestures… Sound is space, because the ear is genetically programmed to interpret audio-information in relation to visual stimuli. What biologically no doubt constitutes a survival mechanism, though, turns into a powerful basis for artistic associations in the hands of Janek Schaefer. Even though Vinyl still plays a vital part on Extended Play, it does so more as a beautiful backdrop of breath for the perfomers to play with – and less as a main musical property. Schaefer has long put his three-armed turntable aside, tired of the circus-like ambiance surrounding it whenever he takes it with him. It’s about time critics and audiences of his work did the same.

(tokafi.com)

Più complesso ed ugualmente spirituale il nuovo progetto di Janek Schaefer, pubblicato dalla Line in contemporanea con “Alone at Last” su Sirr-ecords. Documentazione dell’omonima installazione commissionata lo scorso anno dallo Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, un set di nove vecchie fonovaligie Crosley le quali non solo riproducono vinili incisi per l’occasione ma grazie a modifiche con sensori di movimento captano anche i minimi spostamenti dell’audience e rispondono di conseguenza (l’intero dossier sul progetto, con dettagli, foto, video, suoni etc. è visibile alla pagina), l’opera rappresenta una tappa significativa dell’aspetto più colto del lavoro di Schaefer. Le musiche eseguite in origine da Michael Jennings (pianoforte), Simon Hewitt Jones (violino) e Thomas Hewitt Jones (violoncello), una partitura di dieci minuti elaborata a partire dall’isolamento di un frammento del tradizionale polacco Tango Lyczakowskie e posta su EP opportunamente approntati, vengono automaticamente riprodotte a velocità variabili dai nove giradischi creando di volta in volta fittizie combinazioni strumentali – rumori di meccanismi in azione inclusi – in duo, trio e ensemble allargato (la composizione finale è un collage che impiega la citata canzone popolare registrata con l’ausilio di un apparecchio radiofonico degli anni ’40). Esattamente come i differenti passaggi di una vera e propria sonata cameristica oscurata da imprevisto materismo tattile, un fascino compunto in cui l’idea di eleganza non corrisponde per forza a quello di bella grafia. (7/8)

(Blow Up, Italy)